As government pushes ahead with devolution and local government reorganisation, long-overdue reforms to Local Public Audit risk slipping under the radar. Professors Pete Murphy and Katarzyna Lakoma warn that without proper scrutiny, the new audit system could repeat past mistakes — leaving billions in local spending without robust accountability.

Audit provides an essential part of public assurance and accountability arrangements as it assures financial propriety and underpins both public accountability and public assurance. In 2010, the abolition of the Audit Commission, marked a shift from a publicly coordinated delivery model to one dominated by private firms. The subsequent Local Audit and Accountability Act 2014 radically transformed the form and nature of Local Public Audit and transferred its delivery to a small number of international accountancy firms.

The implementation of the Act was almost immediately followed by growing alarm bells about the adequacy of the new arrangements across the local public audit community, including auditors, local authorities, professional and assurance bodies, and academics. In 2015, the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) itself commissioned RAND Europe (2018) to assess the impact of changes to the local audit regime, and this was followed by reports from ICAEW (2019) and a Parliamentary Academic Fellowship report from Professor Laurence Ferry of Durham University (2019), all critical of the new regime.

In response, the government commissioned the independent Redmond Review (2020) which found Local Public Audit arrangements in England had deteriorated to such an extent that they were no longer ‘fit for purpose’ in terms of their accountability and the assurance offered to the Government, stakeholders, and the public. The privatised market was failing to deliver, with £100bn in local government spending unaudited.

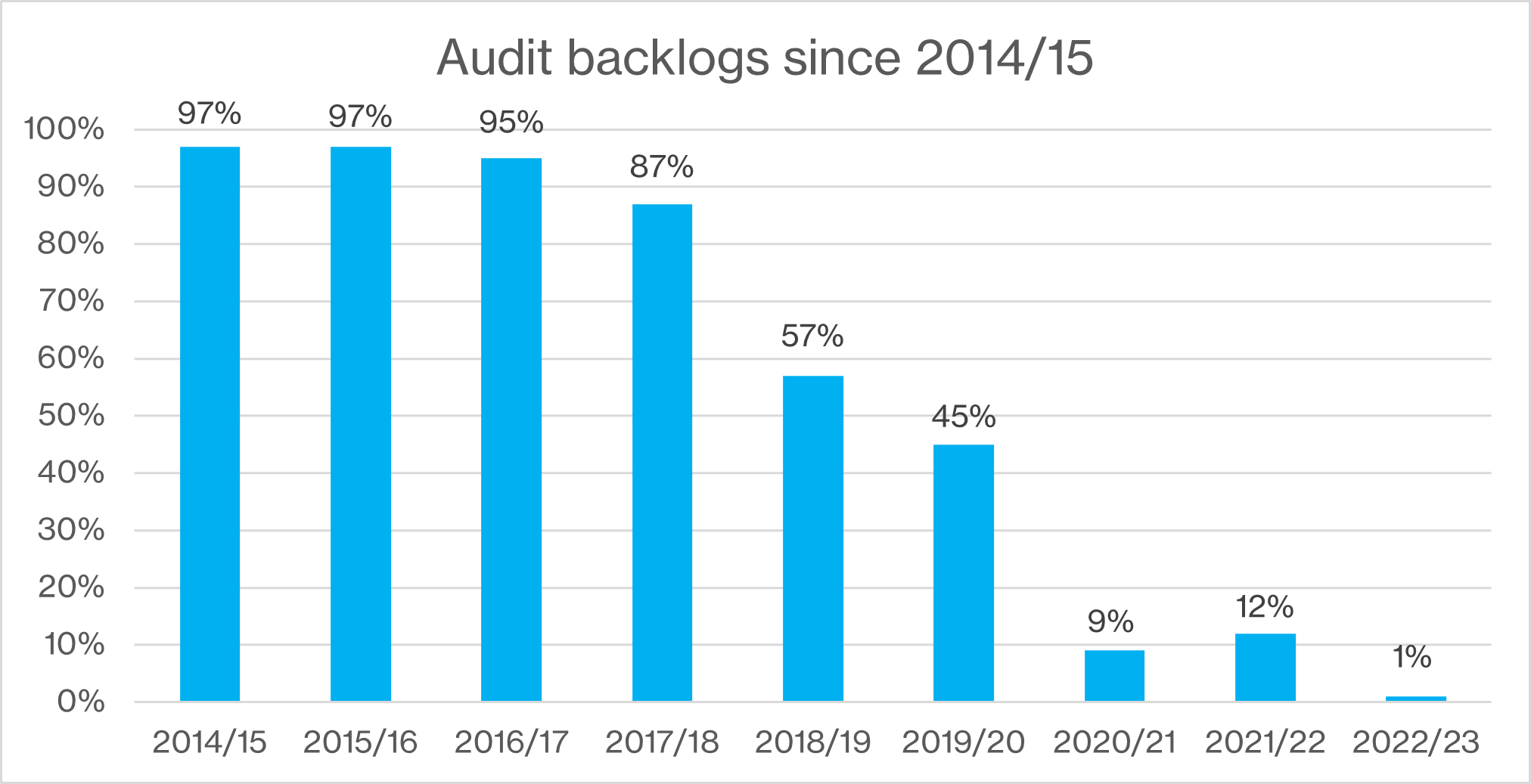

The number of audit reports delivered on time dwindled to such an extent that the National Audit Office (NAO) has for the first time in its history disclaimed the ‘Whole of Government’ accounts (see table 1). The Public Accounts Committee (2023) found that delays stem from the complexity of local government accounts and a shortage of qualified auditors. Redmond recommended widespread changes to the form, nature and content of local audits, to their reporting and to the national leadership, governance and system management arrangements.

Between 2019 and July 2024, three successive Conservative Governments responded and consulted on various changes to the arrangements but took no substantial action, other than late and inadequate attempts to tackle the increasing number of audit delays. The Conservative Government’s most recent response to multiple select committees’ criticisms was a masterpiece of evasion, prevarication, and stonewalling that Sir Humphery himself would be proud of (LUHCC 2024). The government played for time, insisting it was such a complex and difficult long-term issue that it would have to be left until after the election.

Between 2019 and July 2024, three successive Conservative Governments responded and consulted on various changes to the arrangements but took no substantial action, other than late and inadequate attempts to tackle the increasing number of audit delays. The Conservative Government’s most recent response to multiple select committees’ criticisms was a masterpiece of evasion, prevarication, and stonewalling that Sir Humphery himself would be proud of (LUHCC 2024). The government played for time, insisting it was such a complex and difficult long-term issue that it would have to be left until after the election.

However, instead of starting again, the incoming Government proposed to develop a strategy built on the previous Governments’ reviews and stakeholders’ feedback to produce a streamlined system for local audit. In December 2024, it published a consultation and responded to the outcome of the consultation in April 2025.

In July 2025, the English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill, with part 4 devoted entirely to Local Audit, received its first reading in the House of Commons, and in September had its second reading.

The Devolution Bill, which includes provision for local government reorganisation as well as devolution, is undoubtedly a very contentious bill. Local Public Audit reform is probably the least contentious part of the bill because of the prolonged gestation of the proposals and the widespread agreement of the need for change. One possible consequence of this situation is that the audit reforms risk being overlooked, or more likely under scrutinised, and while the principles and intentions appear to be sound, there is a lack of detail and much ambiguity in the bill that needs nailing down.

A new Local Audit Office is intended to provide system leadership, centrally manage audits for councils, help clear the backlogs and ensure high standards in the future. It will (apparently) be independent and responsible for appointing auditors, monitoring quality, and publishing national reports. It will also re-create a public audit service and develop career pathways to attract talent. In due course, it will be applied to a wider group of locally delivered public services beyond local authorities, such as police, fire and rescue services, and national parks. In the long-term the Government will work with the NAO and the devolved administrations to ensure future accounting practices are consistent across the UK.

However, many details and clear commitments are still required, for example we need to ensure that the proposed new arrangements can cover new commercial and hybridised forms of local authority activity. The regime needs to integrate the emerging concepts of financial resilience, sustainability, and vulnerability. It also needs to cover the medium and long-term as well as the short-term, and while the current emphasis is primarily upon retrospective audits this needs to be balanced with more forward-looking prospective accountabilities.

Local Public Audit is too important to be drowned out by devolution and local government reorganisation. The new proposals require public debate and adequate scrutiny if they are to be robust and long-lasting.